Free shipping across Canada 2 bags or 1kg 🤩

Green Bean Coffee Moisture For Roasting

Last edit Mar 13, 2024 ● Published Mar 13, 2024 ● Jasmin Tétreault

Roasting green coffee beans is science that transforms the raw, green seeds into the richly flavored beans that coffee enthusiasts treasure. Central to this transformation is the moisture content within the green beans before they hit the roaster. But what happens when this crucial factor is pushed to its limits? Through an experimental journey, involving the drying of 1kg of green coffee in an oven to a mere 2.8% moisture content, we delve into the impact of moisture on coffee roasting, flavor formation, and the resulting quality of the brew.

Humidity in Coffee Beans

While green coffee beans ready for roasting might appear dry, they inherently contain moisture. Initially, after harvesting, a bean's moisture content is between 45–55%, which processing and drying reduce to 10–12%. The International Coffee Organization guidelines suggest a moisture content of 8 to 12.5% for dried beans.

Yet, for specialty coffee, a 9% moisture level isn't ideal. Moisture levels of 10–12% are generally preferred for enhancing aroma and taste, with many experts and the International Trade Centre recommending 11% and 12% respectively.

Despite the threat of moisture loss due to climate changes during transit, maintaining stable humidity ensures the beans preserve their moisture until roasting. Technological advancements continue to combat this challenge, though it remains a difficult aspect of coffee trade to control.

Coffee Drying Process

In specialty coffee farming, cherries mature at different rates. Farmers inspect crops several times during harvest, picking only ripe cherries. Consequently, beans dry at different rates. Labeling and moisture monitoring of each batch is essential to avoid blending batches, ensuring consistent roast quality.

Drying methods range from mechanical dryers to raised beds, with the latter preferred for optimal airflow and mold prevention. In cooler climates, ground heat from patios aids drying, though it necessitates regular raking to ensure quality.

Over Drying

Over-drying coffee beans significantly affects costs and quality. When moisture falls below 8%, farmers may over-pack sacks to offset weight loss and losing coffee in the process. Furthermore, optimal moisture is essential during roasting for even heat distribution, preventing the outer bean from roasting too quickly and leaving the inside undercooked with undesirable flavors. This is what we have tested.

Under Drying

For trading, coffee beans need to have a moisture content of 12.5%, considering the weight-based trade and the impact on profit. Exceeding this moisture limit risks future business relationships and the integrity of the coffee due to the potential for mold growth, which can spoil even the highest-grade coffee beans. Proper drying and storage are critical to preventing such quality issues.

Moisture During Roasting

It's a common misconception that there is three phases of coffee roasting. The drying stage, browning stage (maillard) and development stage. Those stages are misleading and studies show that coffee dries all the way to second crack.

Same goes for the Maillard reaction, which picks up on speed around 150°C and intensifying until the roast end. There is no isolated Drying or Maillard phase.

The Experiment

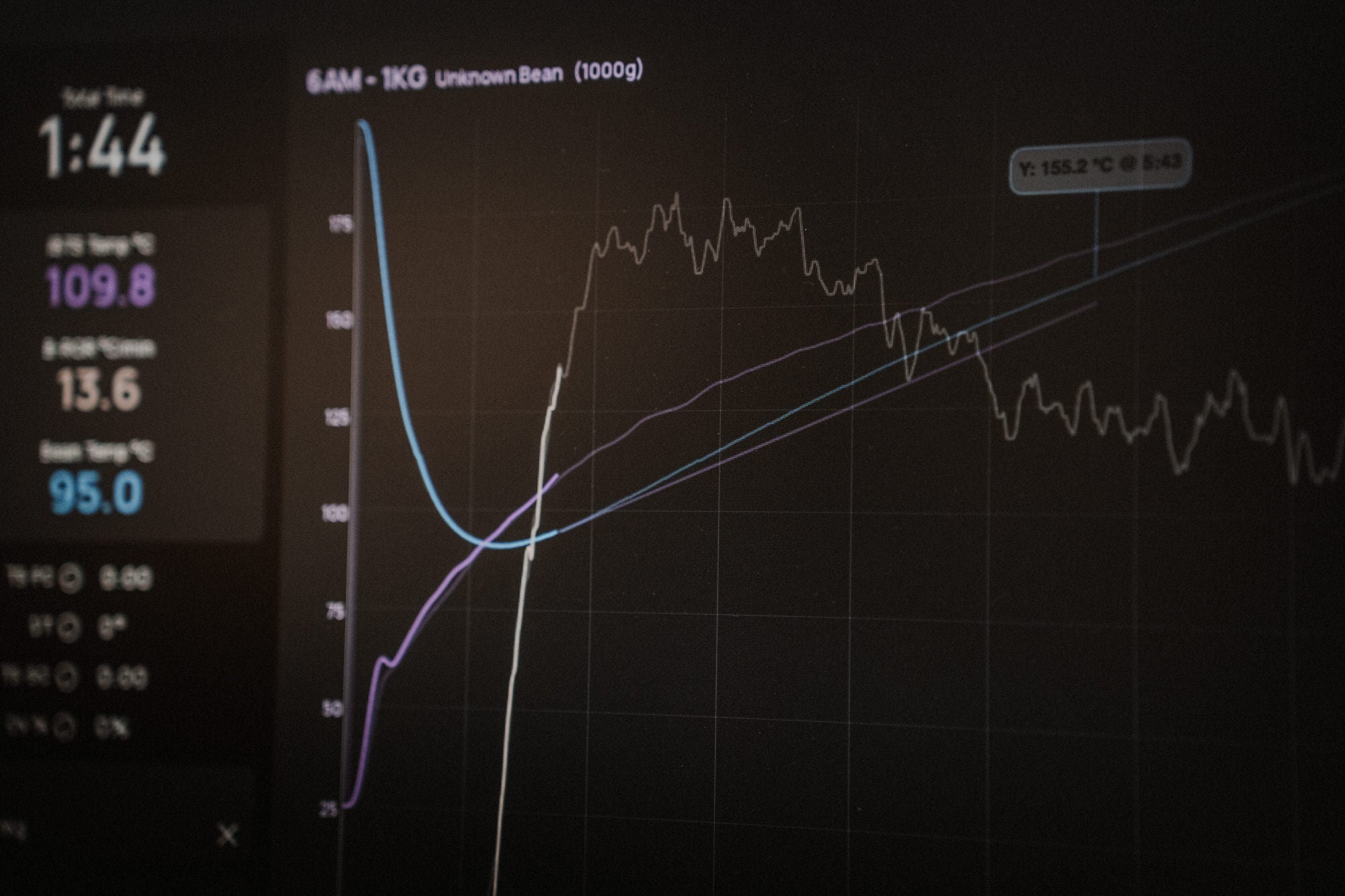

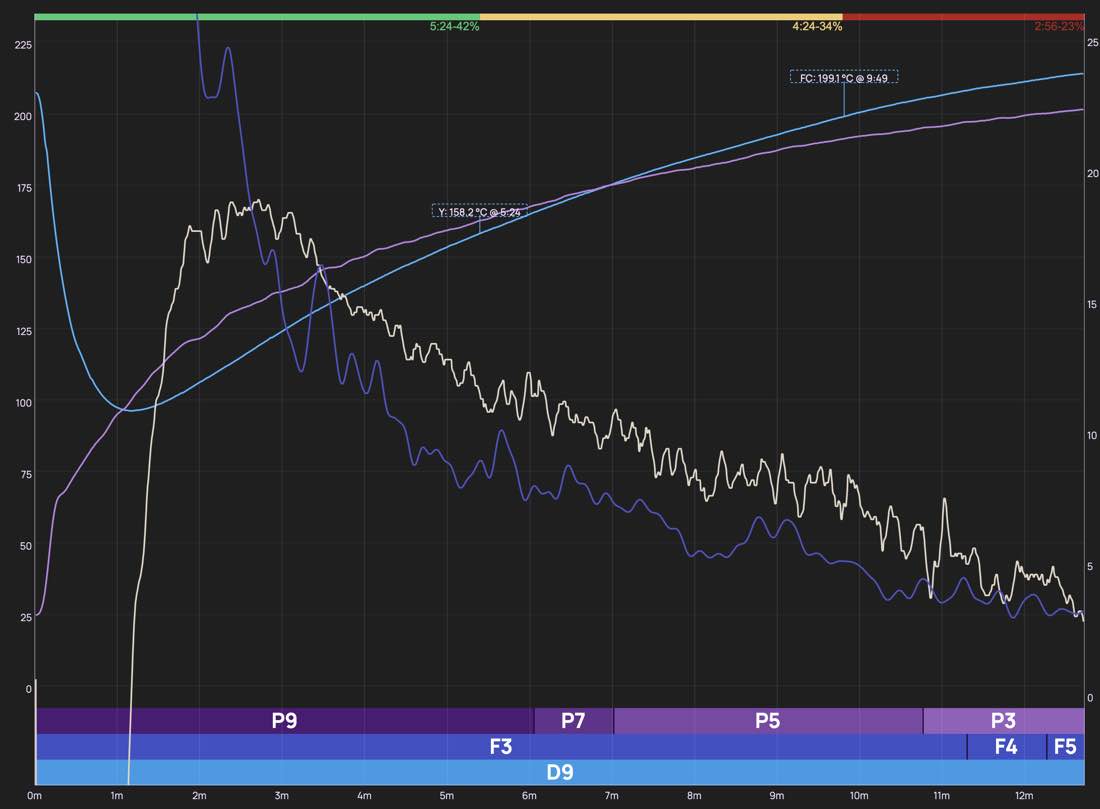

Inspired by Samo Smrke's research into the effect of humidity on coffee roasting, we dried one kilogram of green coffee to 2.8% humidity. The coffee was roasted in our Aillio Bullet, following a profile adapted to normal humidity levels.

The Role of Moisture in Coffee Roasting

Moisture in green coffee beans is not just a passive element; it plays a pivotal role in the roasting process, influencing heat absorption and contributing to the Maillard reaction—a key chemical process that develops the coffee's aroma and brown color through the interaction of amino acids and sugars. According to Smrke, this reaction's intensity is dependent on water activity, peaking at a water activity level of 0.6, with its efficacy dwindling in drier conditions.

During roasting, up to 5% of the bean's weight is lost as chemical water, a byproduct of roasting that facilitates bean expansion, the Maillard reaction, and the development of a porous structure essential for creating the coffee's body and crema in espresso.

Findings

Roasting the overly dry beans was a challenge, with a significant risk of overshooting the desired roast level. The end product was still coffee. Despite the coffee being very dry the beans still expanded and produced a crema upon extraction, from retained CO2.

Interestingly, the aroma of the coffee was noticeably different from that of beans roasted under standard moisture conditions. The difference showed the impact of moisture content on flavor profile development. Smrke notes that this variation could also be attributed to the altered dynamics of the Maillard reaction and other chemical processes during roasting due to the reduced moisture content.

Conclusion

The experiment shows that moisture in green coffee beans plays a role in the roasting process. Although beans with very low moisture levels can still be roasted into coffee, dryconditions significantly affect the coffee's flavor profile. This process emphasizes the critical role of moisture in achieving the coffee's signature aroma and quality.

The ultimate key to making perfect coffee?

Freshly electric roasted specialty beans

Eldorado - Best seller for 3 years

An affordable specialty coffee from Brazil. Medium roast with comforting chocolate aromas. Ideal for a well-balanced, smooth, and comforting espresso.

Eldorado is produced by the Barbosa farm in Brazil, a partner of Nucleus for 3 years now.

Comments

There are no comments.

Your comment